- Diastereomers are stereoisomers that are not mirror images of each other

- If a molecule has n stereocentres, then there are up to 2n possible stereoisomers.

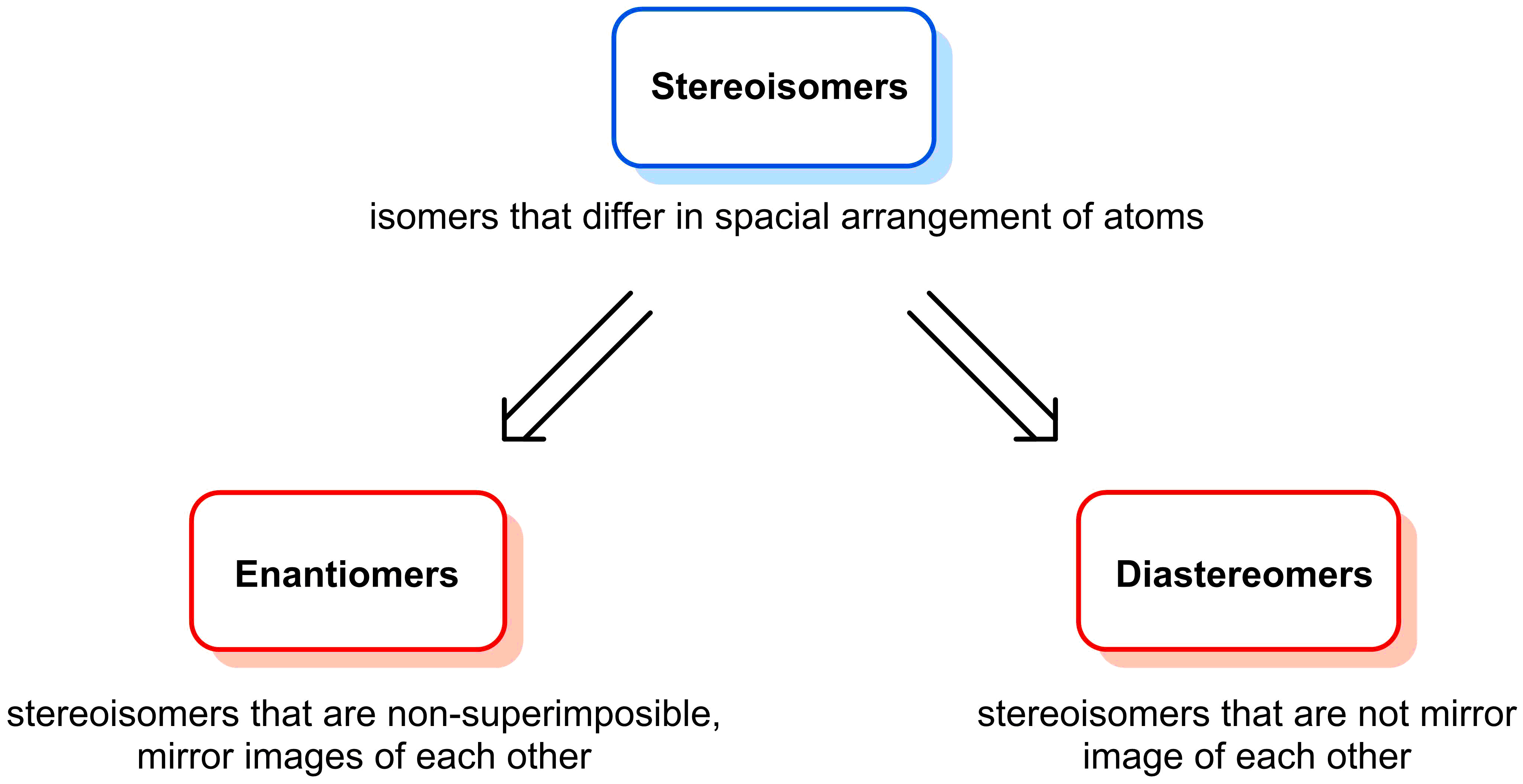

As was previously mentioned in Section 2.1, stereoisomers can be subdivided into two categories: enantiomers and diastereomers. Enantiomers we defined as molecules that have the same molecular formula (isomers), and the same connectivity (stereoisomers), but are non-superimposible mirror images. In contrast, diastereomers are defined as stereoisomers that are not mirror image isomers.

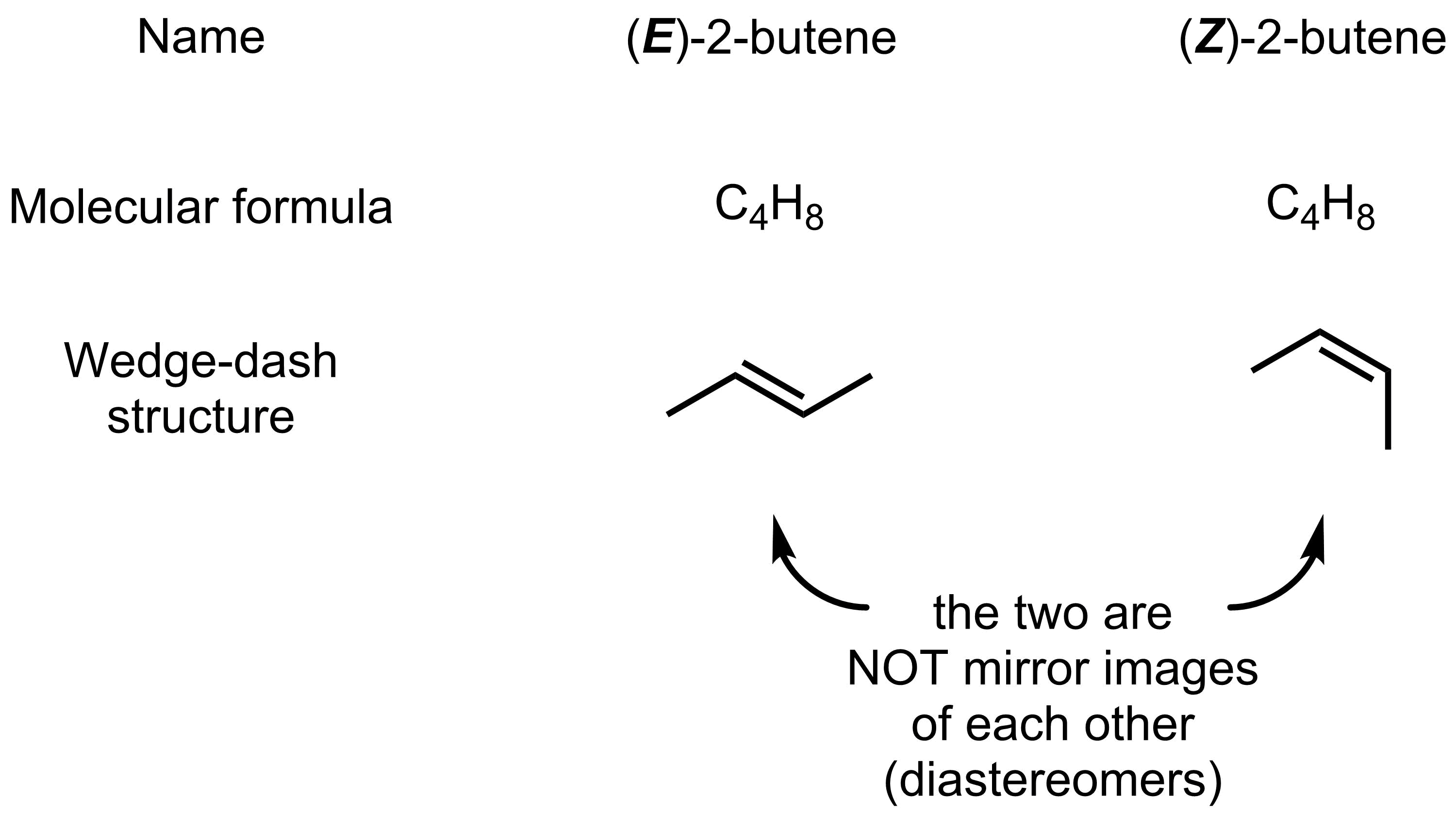

While we did not label them as such, we have already seen an example of diastereomers in the context of alkenes. Take (E)- and (Z)-2-butene. These molecules have the same molecular formula and the same connectivity. The only difference is the arrangement of the atoms in space, which makes them stereoisomers. As they are clearly not mirror images of each other, they are diastereomers.

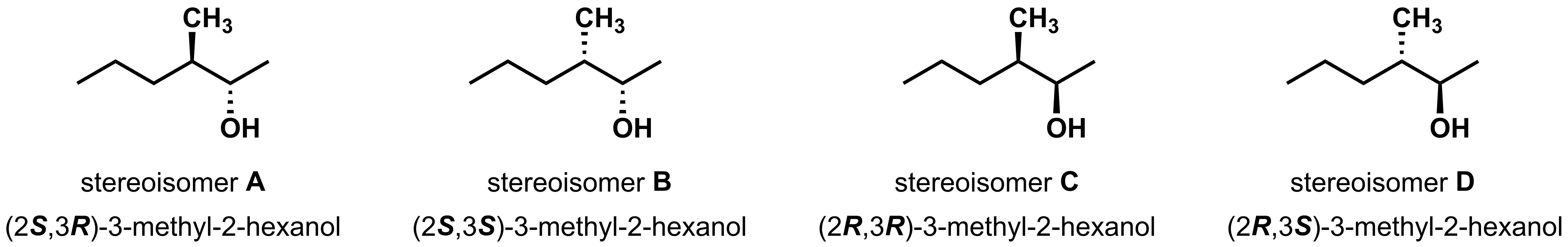

Diastereomers can also arise in molecules with multiple asymmetric centres. Take 3-methyl-2-hexanol, shown below. There are four different ways this molecule can be drawn. Let's start with stereoisomer A. The first thing to look for is its enantiomer (the mirror image). Stereoisomer D is the mirror image, which is easiest to see after a perspective shift. If A and D are enantiomers and all four molecules are different, then A and B, and A and C must be diastereomers. Similarly, B and D and C and D are diastereomers. Stereoisomer B and C are enantiomers.

To name these four stereoisomers, follow the same steps as you learned in the previous section for each stereocentre. For example, for stereoisomer A, the first stereocentre has an (S)-configuration and the second stereocentre has a (R)-configuration. Therefore, this molecule is named (2S,3R)-3-methyl-2-hexanol. Once you have assigned the R/S configuration for one, the other stereoisomers can be labeled by analogy.

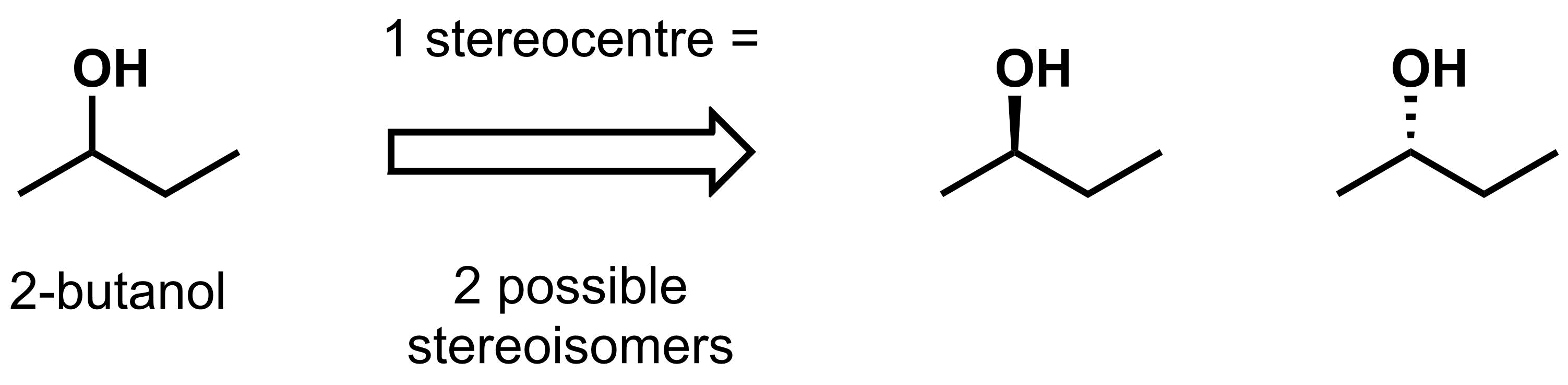

An useful equation to help you draw all stereoisomers of a molecule is as follows:

- number of stereoisomers is at most = 2(number of stereocentres)

For example, 2-butanol has 1 stereocentre, and therefore has 2 possible stereoisomers.

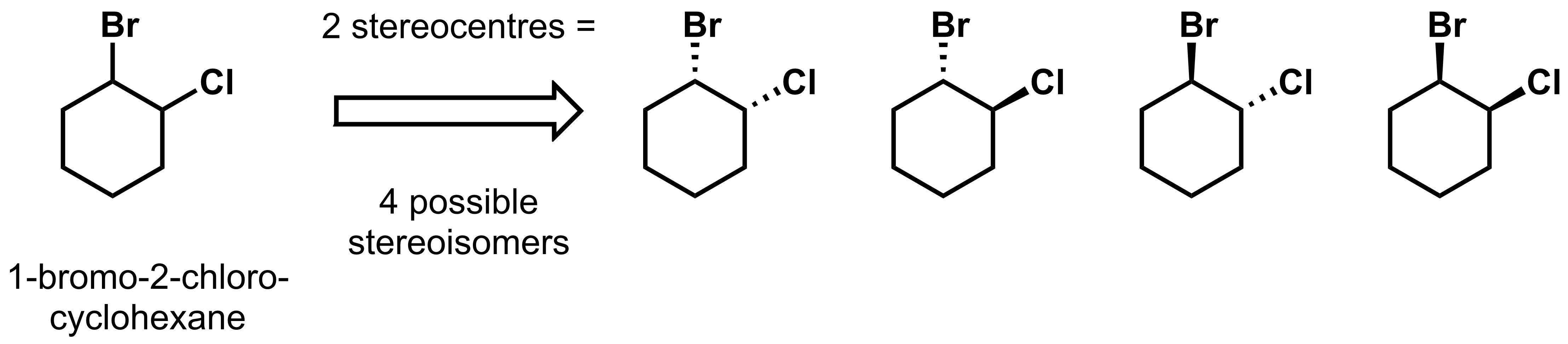

As another example, take 1-bromo-2-chlorocyclohexane. There are two stereocentres, so the molecule has, at most, 4 stereoisomers. The four possible stereoisomers are shown below.

Interactive: